History of Pieczonka’s Tarantella in A Minor

There

is no doubt that the Tarantella in A

Minor was the composition that made Albert Pieczonka

(1828-1912) famous, especially in

the United States. And for good reason. For over a hundred years, it has appealed to

students of all ages with its flashy idiomatic figurations, pianistic style,

technical ease, and tuneful melodies. Pedagogically, it is in a class by itself

in terms of motivating students to tackle more challenging master works. It is a flashy piece that is fun to play. In 1890, Ernst Pauer, the distinguished Viennese pianist, music reviewer and professor of piano at the Royal College of Music in London, reviewed Pieczonka’s Tarantella in A Minor for the Monthly Musical Record (London, July 1, 1890, page 151): “This

bright, lively, and brilliant piece deserves attention; its execution does not

offer any difficulty; its proper expression is easily

understood; and, if played in the proper time and with sufficient fire and

animation, the pupil will earn great applause.”

Pieczonka published the Tarantella in A Minor as the first of his 10 Danses de Salon. The set was

published in 1879 by Augener of London. (There is some evidence that Pieczonka wrote and published the A Minor Tarantella a few years earlier.) It featured mazurkas, waltzes, a fandango, a polonaise

and was framed by two tarantellas that are linked motivically—the

A Minor Tarantella is first and the E

Minor Tarantella is the last dance of

the set. There

is no known existing manuscript of the Tarantella,

so the 1879 Augener edition is the earliest source. A free copy of the Tarantella in A Minor,

published by Augener, can be downloaded from Pianoarchive.org (click here). This 1907 Augener edition from London is very close to the 1879 Augener edition although there is a misprint in measure 196 (see text below) and it has been phrased and fingered by Thümer.

In

1881, Pieczonka immigrated to the United States,

where his Tarantella in A Minor for

piano was quickly becoming a “hit.” By

the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Tarantella

was being mass-marketed and printed simultaneously by several American

publishing houses: Schirmer,

Carl Fischer, Presser, White-Smith, Schroeder & Gunther, Jos. W. Stern

& Co. (edited by Gallico), to name a few. At the time, the United States did not recognize foreign copyrights, so it is doubtful that Pieczonka, who had already published the Tarantella in London, had any connection with this American publishing frenzy. It is equally doubtful that he received any royalties from the American publishers.

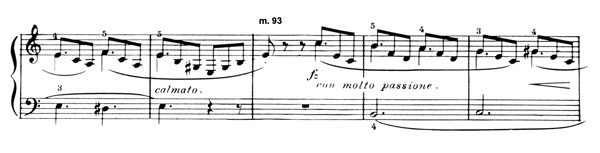

Note and Rhythm Changes Measure 93 Note-wise, most of our current editions of the Tarantella are faithful to the 1879 Augener edition, with the exceptions of measure 93, measures 164-5, and measures 10-11. Sometime around 1900, the notes of these measures were changed and simplified in several of the American editions. Here

is measure 93 as it appears in the original 1879 Augener

edition:

Below

is measure 93 as it appears in most American editions dated after 1900

Indeed

the half cadence followed by silence, from the post-1900 American editions, is

very different from the authentic cadence and continuous 8ths of the original

London edition. The source of the

altered measure has yet to be discovered.

Perhaps it was just an editorial simplification that became popular.

It is interesting to note that the 1887 American edition by White-Smith Publishers and the 1895 American Schirmer edition are both faithful to the first edition in measure 93. (As expected, the post-1900 London Augener edition retains the original notes to measures 93, 164-5 and 10-11.)

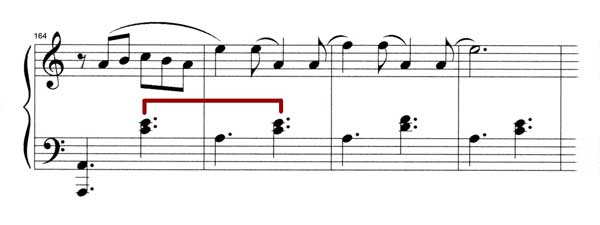

Measures 164 to 165 For the return of the main theme in measure 164, Pieczonka originally added an inverted pedal point—i. e. two voices in oblique motion—to the accompaniment, as seen in the 1879 London Augener edition.

In many current American editions, this accompaniment has been simplified, as seen here:

Over the years, the original version has been strongly favored however—including American editions like the Schirmer edition (1895), The University Society (1903) and Century Publishers (1908 )—and appears in at least one of the current editions today. Even in some of the American editions that had simplified measure 93, this original accompaniment in measures 164-5 can be found.

As with the case of measure 93, there is no documentation as to how or why this simplification was made.

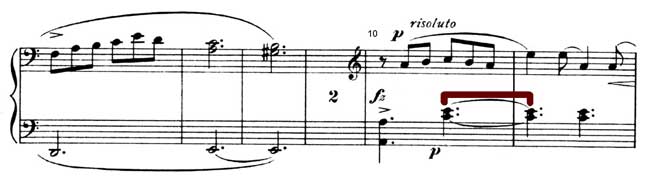

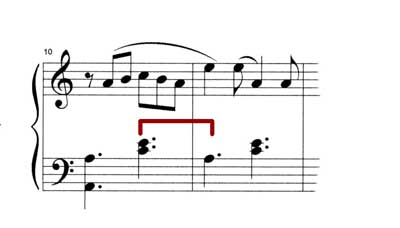

Syncopation in Measures 10 to 11 A quick survey of the Tarantella’s A section reveals several syncopations in the accompaniment—measures 23-4, measures 65-6, and throughout the broken octave passage measures 26-42, which ends with a remarkable chain of syncopations in measures 38-42. What is missing in most of our current editions is the very first syncopation of measures 10-11. In the original 1879 Augener edition, Pieczonka actually opened his famous Tarantella melody with a syncopated accompaniment, as seen here:

Replacing this initial syncopation with the straightforward broken chord accompaniment we commonly see today was one of the first changes made by most of the American publishers post-1900.

Of the historic American editions I have examined, only one edition retained this original, first syncopation: the White-Smith edition of 1887. Measure 196 The left hand accompaniment in measure 196 appears changed in only the 1907 Augener edition from London.

Since this measure is identical to measure 192 in every other edition I have seen—historical and current—I have come to the conclusion that it is a misprint. It should have been a repeat of measure 192. Influence of

Chopin on Pieczonka’s Tarantella

A

quick survey of the titles of Pieczonka’s works for

piano reveal the unmistakable influence of a contemporary pianist/composer,

also of Polish heritage: Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849). Chopin died just as Pieczonka

was leaving the Leipzig Conservatory in 1849, but his compositional legacy had

a big impact on Albert Pieczonka. Chopin’s

Tarantelle

Op. 43 (1841) was an obvious inspiration to Pieczonka. In fact, Pieczonka

chose the French spelling, Tarantelle, when

he first published his Tarantella in A

Minor in 1879. For many years it was

often identified as the Tarantelle in A

Minor. A quick comparison of Pieczonka’s work to Chopin’s Tarantelle reveals some striking similarities. For example:

the short introductions, the initial melodic contours, and the sudden,

punctuating octaves (in measures 20 and 28) followed by flashy descending

figures.

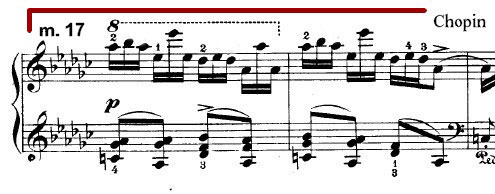

In addition, one does not have to look far for a Chopin-inspired antecedent of Pieczonka’s splendid, glittering passage in measures 26 to 42. Although there is a brief hint of this pattern in measure 224 of the Chopin Tarantelle

I

believe that Pieczonka actually looked to an earlier

work by Chopin for inspiration: measures 17-18 of Chopin’s Etude in G-flat Major Op. 10, No. 5 Black Key (published in 1833).

Whereas the Chopin Etude

requires the pianist to leap from pattern to pattern on black keys, Pieczonka’s much easier version uses the same pattern on

contiguous white keys.

© Stephen

Erickson August 9, 2012 |